I'm a software engineer by trade, so I spend a lot of my day working with code.

When I step back and take the 50,000 foot aerial view of my job, I realize that programming is basically an exercise in managing complexity.

It's hard to convey to non-engineers just how devilishly complex software can be. When you're on the outside, as the user of a piece of software, it mostly Just Works(tm). But from the inside, as someone building it, it looks more like a sausage factory.

The code for a medium-sized application — a calendar app, for example — can be hundreds of thousands of lines long, split across thousands and thousands of files. As an engineer, you can fit about 50 lines of code on your screen at any one time, and hold maybe 1000 lines in your head (if you have a good chunk of uninterrupted quiet time).

Each line of code specifies an action that the computer is going to take when it executes that line. Actions range from extremely simple — add two numbers together — to unfathomably complex — do whatever it takes to fetch a particular piece of data from halfway across the world and copy it to the computer's memory, or if that fails, for any reason, execute this other piece of code that will attempt to figure out what went wrong. (That's the English translation. It probably looks more like this: getData(uri, buffer, callback).)

So there are hundreds of thousands of lines of this stuff, and you can only fit about 50 lines on your screen at any one time. It's like squinting at a battleship, up close, through a cardboard tube. Except the ship doesn't stand still, because while you're looking at it and poking it and changing one thing at a time, your teammates — dozens or hundreds of them — are making their own changes to it. Yesterday, when you aimed your little scope up and to the left, you thought you saw the signal bridge. But today it's not there. Did you really see it yesterday? Did someone move it? Either way, now you have no idea where it is, but maybe it doesn't matter. You're just trying to mount this turret. Now where did the screws go?...

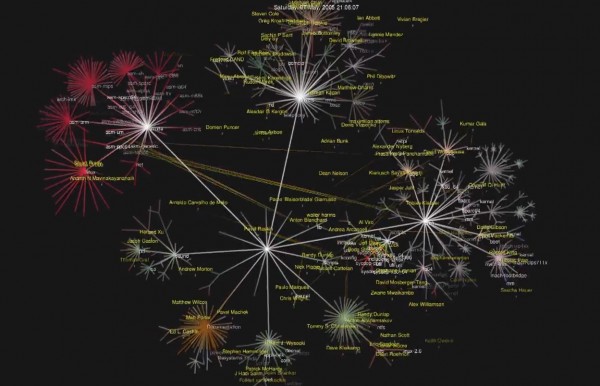

Above: A "code swarm" visualization of the development of the Linux kernel. Video here.

****

Navigating the human social world has almost nothing in common with building a piece of software. From a cognitive perspective, empathy and analysis may in fact be mutually exclusive. But the social world shares at least one feature with the world of code: intractable complexity.

Both software and society have too many moving, interdependent parts for any one person to fully understand, let alone predict how they'll behave in the future. The best you can do is try to maintain a fuzzy version of the "big picture," and concentrate on understanding your small, local piece in enough detail to get by.

Now, here's what I find very interesting.

Faced with the challenge of acting in an intractable world, engineers and social creatures have devised similar tools for coping with complexity.

As an engineer, one of the most important skills you develop in your career is a 'nose' for code. With a well-calibrated sense of 'smell,' you can quickly take stock of whether a piece of code is healthy or diseased, by using a 'sniff test.' A good nose, in other words, helps you detect lurking danger.

This sense has been catalogued into a set of bad code smells. A code smell is a surface-level indicator of a potential deeper problem. A 500-line method, for example, might not be causing actual bugs (in its current state), but it's going to be tricky and fragile and it might blow up in your face. If you're working with code that doesn't smell right, you need to be extra careful because any change you make can lead to unintended consequences. A bad smell is a warning sign that you should spend extra time and effort to understand what's going on as thoroughly as possible. And if you find yourself writing code that smells bad, you'll want to think very carefully before committing it. Bad smelling code isn't always wrong, but you should make doubly or triply sure there isn't a better way.

In the human world, we also have a 'nose' that can sense lurking danger in social situations: moral intuition. When something doesn't feel (or smell) right, it doesn't automatically mean there's a problem, but it's definitely cause for concern. A conflict of interest, for example, isn't necessarily wrong (per se), but it's a surface-level indicator of a potential deeper problem, and it warrants special attention/caution. And if you're thinking about taking an action that doesn't smell right to you, you should think twice or three times before acting, to make sure you really understand the consequences. Even then, it might be wiser to admit fallibility and just follow your nose.

Like code smells, our moral intuitions are valuable heuristics for understanding the world, especially in dangerous situations. Heuristics (by definition) aren't perfect, but they're useful because they're easy to apply and are usually more accurate than trying to calculate things 'by hand'.

****

Just as we've catalogued bad code smells, we can catalogue bad ethical smells. Here's a partial list, which is meant to be more suggestive than definitive:

- Conflict of interest: a situation where incentives pull in the opposite direction from responsibilities.

- Moral hazard: when benefits are paid out to a different party than the one who assumes the risk.

- Lying/deceit: causing a person to believe something that isn't true. Lying isn't always wrong, but it's a warning sign of something potentially bad. (Remember, these are heuristics, not perfect signals.)

- Harm: any situation where someone is getting hurt.

- Censorship: when people are afraid to say what they believe (odds are that something's amiss).

- Deviant behavior: behavior that violates the norms of the community. Again, deviance isn't always wrong, but it may be a sign that someone hasn't properly internalized the norms of the group. (Or maybe the norms are wrong — either way, it's worth investigating!)

- Dehumanization: when a person or group is treated as less than fully-human. Quite often this is an excuse to mistreat them.

And so on. It would be fun to catalogue more of these, but I hope I've illustrated the point.

And just as good engineers hone their sense of smell over the course of their careers, people hone their moral intuitions over the course of a lifetime. This begins when we are very young, and stories play a huge role in helping us see the patterns. As Robin Hanson has noted on a number of occasions, stories are vessels for moral information. A scenario is presented, often involving one or more bad ethical smells, and then we get to watch the consequences play out.

****

Programmers are notorious for their overconfidence. We overestimate our skills, underestimate the difficulty of problems, and routinely build systems that become too complex for us to manage. As Brian Kernighan famously put it:

Debugging is twice as hard as writing the code in the first place. Therefore, if you write the code as cleverly as possible, you are, by definition, not smart enough to debug it.

People are likewise overconfident in the social world. We all think we're smarter than average, and we're always willing to make an exception for ourselves because — hey, don't worry, we know what we're doing! Except that we usually don't.

We're good at calculating, but not as good as we think we are. We're too clever by half and prone to hubris.

That's why it pays to develop a good sense of smell.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt