Why do humans dress up in funny clothes and perform elaborate actions with no tangible effects?

Remember, we're not just human beings — we're apes. Why do apes do this?

A study of ritual in ten lessons.

I. indirection

A coronation ceremony is a "ritual" in just about every sense of the word. So are activities like the national anthem, a homecoming rally, and a Muslim's five daily prayers. A handshake, a birthday gift — even saying "hello" is considered a ritual.

What about brushing one's teeth?

This question has always amused me for prodding the concept of ritual in just the right way to elicit insight.

Certainly there's something ritual-ish about the act of brushing one's teeth. A ritual, if we take Wikipedia for the consensus definition, is

a sequence of activities involving gestures, words, and objects performed according to set sequence. Rituals are characterized by formalism, traditionalism, invariance, rule-governance, symbolism, and performance. [modified slightly for clarity]

Tooth-brushing hits pretty much all of these points. A sequence of activities? Check. Invariance? Check. Rule-governance? Yep — circular motion, two minutes, touching all teeth and gums.

(Symbolism? Perhaps not so much. But hand-shaking isn't symbolic either, and yet it enjoys excellent standing as a ritual.)

The problem with tooth-brushing — what keeps it from being recognized as a full-fledged ritual — is that it's too technical. Its aims are too concrete; its means, too direct. Unless we're prepared to admit all human behaviors to the sacred order of ritual, we have to exclude some of them, and the first criterion for exclusion is when a behavior is too straightforward. Proper rituals are always a little mysterious, a little indirect.

"That a behavior is 'ritual'," says Sarah Perry, "is a hypothesis presented when the behavior appears irrational."

So: brushing one's teeth, lacing up one's shoes, buying groceries, taking a flight, getting a haircut, taking the bus to school, even Amish barn-raising — prima facie, none of these are "rituals." The label only applies when the behavior in question doesn't seem straightforward, when we sense that there are hidden agendas or hidden forces at work.

Of course a behavior need not be purely technical or purely ritual; some behaviors will be hybrids. A trial by jury, for example, is highly technical, and yet it's overlaid with enough formal, traditional, theatrical elements that it could equally be called a ritual.

"More than meets the eye," perhaps, is a good slogan for what we're trying to study.

II. Not superstitions

But however mysterious, however seemingly irrational, rituals aren't useless superstitions.

Rituals are everywhere. They can be elaborate and very, very expensive. In some cases, they're preserved unchanged for millennia.

All of this argues for some real utility being delivered.

Certainly some rituals may be perfectly useless superstitions — like throwing spilled salt over one's shoulder, for example, or shaking a Polaroid. But truly pointless rituals are rare. People have a keen sense for when they're being jerked around (versus when their interests are being served), and a practice that does nothing is easily abandoned. Most rituals pay out, somehow or other.

In Surely You're Joking!, Richard Feynman memorably describes the cargo cults that sprang up among Melanesian Islanders after contact with Western cargo shipping practices. "During the war," he says,

[The Melanesians] saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they've arranged to imitate things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas — he's the controller — and they wait for the airplanes to land. They're doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn't work. No airplanes land.

[Here's a video, if you're curious.]

A cargo cult, in other words, imitates only the trappings of functional cargo shipping practices. It's form divorced from function, superstition run amok, an exercise in utter futility.

At least that's the conventional view.

I would take a different approach. I'd sooner look for some hidden value to the cargo cults, before laughing them off as useless superstition. It's certainly possible that the Melanesians are completely wasting their time — but it's also possible they're getting something out of it. If we casually dismiss their acts of worship simply because their god, the God of the Metal Birds, doesn't exist, then we should be equally dismissive of Westerners who pray to the God of the Ancient Shepherds — and I'm not prepared to do that.

When taken literally, both cargo cults and "legitimate" religions are equally quixotic. No airplanes are summoned, no prayers answered. But religious practices should never be taken literally.

Most of my life I've been dismissive of theology. If there are no gods, then it's all an elaborate waste of time. As a field of study, theology must be as intellectually bankrupt as they come — right?

Now I'm beginning to think otherwise. We, human beings, have an uncanny ability to dislocate our minds, to grasp at our own intuition by means of symbolic indirection. Yes, it's ontological nonsense to say that kids should respect their parents "because God commands it." But Confucius arrived at similar principles without an appeal to the supernatural, so the conclusion itself has merit, however spurious the argument.

By the same token, we might wonder why the early Christians obsessed over the nature of the Trinity. How could it possibly matter whether the unreal godstuff being worshipped is three-part or whole? But of course, such arguments aren't really about the nature of the Trinity. The early Christians were simply using the Trinity as a proxy battleground in their squabbles for influence among competing sects. (Those first three Christian centuries were a heady time.)

Theology may look like cargo-cult philosophy, but there's a more fruitful way to look at it: as a continuation of politics by other means.

III. culturally-evolved magic

Here's a sorely underappreciated idea:

Humans are better at sensing whether something is working out in their favor than understanding why or how it's working out.

For example, you don't need to understand why it's useful to welcome guests when they arrive (e.g. with a hug or a handshake) to appreciate that it's a good idea. All you need to know is that it creates good warm fuzzy feelings when you do it, versus awkward vibes when you don't.

These kinds of unjustified, "irrational," black-box behaviors exist because of a simple fact of human psychology: Our brains were built to form quick, binary judgments about everything we encounter, i.e., a positive or negative valence (friend or foe, approach or avoid). Relative to these intuitive judgments, however, verbal explanations are relegated to the position of, quite literally, an afterthought. It's simply more important for our brains to know what is good for us — so we can approach or avoid it, continue the practice or abandon it — than to know why.

Now, take this facility of ours (judgment without understanding), hitch it to the process of cultural evolution (copy what works, discard what doesn't), crank it for a few generations, and out will pop a bunch of practices that do useful things, but which we don't fully understand — i.e., rituals.

So if we don't fully understand them, but they work anyway, rituals must feel like magic. This is the psychology behind Arthur C. Clarke's famous third law:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

And here's the behavioral analogue:

Any sufficiently opaque ritual is indistinguishable from magic.

"Magic," says Bronislaw Malinowski, "is to be expected and generally to be found whenever man comes to an unbridgeable gap, a hiatus in his knowledge or in his powers of practical control, and yet has to continue in his pursuit."

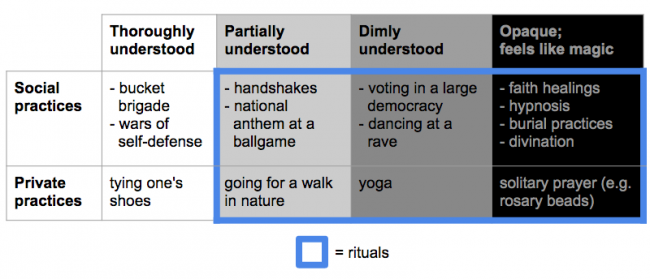

It's important here to get a sense for what this kind of magic feels like, from the inside. It feels like the right-hand columns of this table:

Please don't get hung up on exactly which column I've chosen to put something in. I'm just trying to give a sense for how some things are more mysterious than others — for how rituals feel like culturally-evolved magic.

IV. Inside vs. outside view

Imagine yourself deep in the Amazon rainforest, hundreds of miles from civilization, where you encounter a tribe that practices a peculiar behavior: they brush their teeth. And they do it in a style suspiciously similar to the Western style. They attach bristles to the end of a short stick, rub some pasty gel on the bristles, and proceed to lather up all their teeth and gums. You don't know whether they invented this practice themselves or picked it up from some wandering missionaries in decades past — but it doesn't really matter. When you ask them about it, they tell you they do it to "appease the angry mouth-spirits."

Would we be tempted to call this a ritual? I think we would.

But note that in doing so, we veer dangerously close to a double standard. Aside from dentists, most of us, here in the modern West, don't have a particularly deep understanding of why we brush our teeth. We just use fancier words: instead of "mouth-spirits," we're fighting off "gingivitis" and "tooth decay." But of course (as Feynman said in a different context) simply knowing a name for something doesn't mean you understand it — and I, for one, have no idea what gingivitis is, let alone what causes it.

Now, instead of an Amazonian tribe, imagine our own world a few decades hence. What if scientists discover that tooth-brushing is entirely ineffective at preventing gingivitis and tooth decay? It would mean we've been mistaken all these years, wasting our time on a superstitious practice. Perhaps we were just addicted to that clean-mouth feeling. Or perhaps the daily activity was simply calming and soothing — a minty, two-minute reprieve from the stresses of the world.

In this case, would we be tempted to call tooth-brushing a ritual? Again, I think we would.

But of course this is only possible when we view our own behavior from a hypothetical "outside view." From the inside, given what we (think we) know about dental hygiene, we can't help but see it as a perfectly technical, practical activity.

Lesson: It's easier to see "rituals" in other people's activities, harder to see them in our own.

V. confabulation

Humans are the kind of creatures who, when good explanations are hard to come by, will quickly settle for bad ones; "I don't know" is strangely hard for us to say. This tendency is especially pronounced when it comes to our own behavior.

In a famous series of experiments in the 60s and early 70s, neuroscientists Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga demonstrated just how effortlessly our brains manufacture bogus explanations when the real explanations are inaccessible. By using so-called "split-brain patients," and by carefully controlling the information they presented to each (isolated) half of the brain, Sperry and Gazzaniga were able to "catch the mind with its pants down," so to speak.

In one experiment, for example, they asked a split-brain patient, via the right half of his brain, to get up and walk to the door — and the patient dutifully complied. But when they asked the patient what he was doing, via the left half of his brain, the left brain made up an answer and brazenly tried to pass it off as the truth: "I wanted to go get a Coke."

This is called confabulation: our tendency to fill in the gaps (of our own understanding) with plausible-sounding ideas that we have no good evidence for. And it doesn't just apply to split-brain patients; it's been amply demonstrated in healthy, whole-brained patients as well. When asked "Why?" about a puzzling phenomenon — especially one that involves our own behavior — we'll often make up an answer rather than admit that we have no idea. There's no intention to deceive; we aren't lying per se; but we nevertheless try to pass off an unsubstantiated statement as the known truth.

As you might imagine, rituals attract confabulated explanations like flies to honey. A ritual, remember, is a practice whose causes are poorly understood, a practice attended by an aura of mystery. It's a behavior in need of an explanation, which our brains, by way of confabulation, dutifully provide.

That feeling during a spiritual experience, where (as Maslow writes) "the sense of self dissolves into an awareness of a greater unity" — what is that? What causes it? Not even today's neuroscientists have an answer, so how can we fault anyone for explaining it as "the presence of God." The warmth of fellowship and community, heightened into the feeling of collective effervescence, which in extreme cases can cause people to speak in tongues — again, lacking a good explanation, "God" is a serviceable substitute.

Why do so many human cultures worship dead ancestors? The practice itself is functional in a number of ways — not least of which being that dead ancestors (especially powerful ones) provide a Schelling point for coordination among the living. But that's not how anyone rationalizes it. Instead there are stories about the afterlife, and the need for the living to provision the deceased with grave goods, or to send ghost money as if by Western Union.

The only essential fact is this: Human apes who pay conspicuous respect to their ancestors earn more trust from their fellow apes than those who aren't as pious, so practices of paying conspicuous respect are rewarded and they persist. But none of the apes understand why, so they make up a plausible-sounding explanation.

(This, in turn, puts a bit of pressure on the ritual to adapt to the confabulation. It might not be a stretch, then, to say that rituals and confabulated explanations co-evolve. When we put on clothes, we adapt our posture a little bit in response. Similarly, when we dress up our rituals in confabulated explanations, sometimes the rituals shift a bit to better accommodate their dressings.)

You might think that once a ritual is "explained," it would lose its aura of mystery. I think that's partially true. But I also wonder whether our curiosity is so easily hoodwinked. I suspect that rituals — even ones that have been draped in the finest tapestry of confabulated explanations — will still retain a hint of mystery about them, because people will sense that the official explanation isn't entirely copacetic. There will always be a lingering, inexplicable magic to the performance of a ritual.

VI. Personal vs. social

As we've argued, brushing one's teeth can, in the right context, become a ritual. Kneeling in prayer, too, is a ritual, and it's often done in private. Even taking a walk alone in the woods can be a ritual.

Nevertheless, most rituals, and especially the most elaborate and interesting ones, are social phenomena — unabashedly, orgiastically social. I mean, just look at this:

Some thinkers (e.g. Perry) even go so far as to say that rituals are "fundamentally" social — but that's where I have to part ways.

It may be just semantics, but I prefer to think of "rituals" as fundamentally irrational or mysterious (i.e., hard to explain), and only incidentally social.

Why, then, are rituals so often two–, ten–, or 10,000-person affairs?

The answer, I think, is simply because social behaviors are orders of magnitude more complicated than personal behaviors, and therefore much harder to explain. Social behaviors involve all sorts of weird phenomena: information asymmetries, handicapping, higher-order effects, misunderstandings, outright deception, stable and unstable equilibria, sex, politics, social status, etc. In social life, much more than in private life, our brains find it necessary to take the "black box" shortcut — to throw up our hands and say, "I don't need to understand how this behavior works, as long as it feels good."

That moment at a concert when everyone starts singing along in unison — why is that so thrilling? Where does that feeling come from? Questions like this may be important to the anthropologist, but the part of our brain that gets off on participating in rituals just shrugs. Doesn't matter, it says, warm fuzzies.

Lots of social phenomena are hard to understand and produce strange effects, but four stand out as particularly important drivers of ritual behavior. These are:

- Mimicry (or synchrony)

- Common knowledge

- Sacrifice

- Strategic ignorance

Let's look at each of them in turn.

VII. Mimicry/synchrony

Modern armies no longer line up in neat rows and charge each other from opposite sides of a battlefield. But, strangely, they still train that way:

This practice is incredibly useful, it turns out, not to prep for actual battle conditions, but to build trust and solidarity among soldiers in a unit.

Our species, for whatever reason, is wired to form social bonds when we move in lockstep with each other. This can mean marching together, singing or chanting in unison, clapping hands to a beat, or even just wearing the same clothes. In the early decades of the 20th century, IBM used corporate songs to instill a sense of unity among their workers. Some companies in Japan still use these practices today.

Consider the high five. It's a simple act, but it involves both physical synchrony (getting your hands to align in time and space) and emotional synchrony (both people need to be in a good mood). After giving someone a high five, you're likely to feel happier and more like part of the same team. (But if you try giving a high five to someone in a bad mood or someone who doesn't like you, you'll sense their resistance to synchronizing with you.)

Stanford psychologists Scott Wiltermuth and Chip Heath recently demonstrated the synchrony/solidarity effect experimentally. They first had groups of students perform synchronized movements (such as marching around campus together), then had them play "public goods" games to measure the degree to which individuals were willing to take risks for the benefit of the group. What they found is that:

Across three experiments, people acting in synchrony with others cooperated more in subsequent group economic exercises, even in situations requiring personal sacrifice.

Mimicry is a closely related phenomenon, a kind of time-shifted synchrony: Person A does something, then Person B copies it at a later time.

Like synchrony, mimicry creates trust between the two parties, but unlike synchrony there's directionality involved; Person B is copying Person A, rather than vice versa. This shows that B is open to influence from A. Thus low-status people tend to mimic high-status people more often than the other way around. And rituals involving mimicry can thereby be used to cement authority and obedience in addition to flat solidarity.

Mimicry also allows authority/obedience to span years, decades, or even centuries. When a coronation ceremony harkens back to the previous coronation, it's a way of anchoring authority in tradition, the past, the way of one's ancestors.

VIII. common knowledge

In Rational Ritual, Michael Chwe illustrates how the phenomenon of common knowledge underlies a lot of our ritual activities.

For a fact to be common knowledge, it's not enough simply for everyone to know the fact. Everyone must also know that everyone else knows it, and know that they know that they know it, and so on.

Consider life under an oppressive regime — in North Korea, say. It's possible that every North Korean citizen knows, from firsthand experience, that the ruling regime is oppressive and terrible — but such knowledge would not be common knowledge. It would be (to coin a phrase) closeted knowledge. It's something that everyone knows privately, but no one is certain that everyone else knows as well. And crucially for the North Koreans, when knowledge is closeted it prevents everyone from acting together, e.g., in a rebellion.

How does knowledge come to be so closeted? In part, it's because leaders use massively public rituals to create the impression that everyone is happily obedient. When hundreds of thousands of citizens show up to celebrate Dear Leader, it's hard not to suppose that a good fraction of that sentiment is genuine. It's an elaborate, modern-day version of the "kiss the ring" ritual.

The Pledge of Allegiance, by the way, as well as singing the national anthem at a ballgame — these are similar tactics, and they have a similar effect. The two primary differences are that (1) loyalty in the U.S. is directed primarily to the nation rather than the President, and (2) the loyalty among Americans is more genuine than that of the North Koreans (or so we suspect).

But regimes that live by the sword, die by the sword, and rituals of mass public participation can just as soon topple as prop up a precarious regime. The reason public protests and demonstrations are so potent isn't just because the crowd might turn angry and storm the gates. It's because when you get all those people together — people who are risking injury or jail just by showing up — it creates instant common knowledge of how unpopular the regime has become. Everyone who shows up at the protest knows that everyone else knows that... it's time for change.

A fig leaf of popularity, backed by an implied threat of violence, can cow every citizen individually, keeping their true feelings closeted in their thoughts, homes, and small social circles. But a fig leaf is no match for a large chanting mob.

IX. sacrifice

Q: Who do we want as allies? A: People who are willing to put our interests ahead of their own. The more someone sacrifices for us (or in the name of our group) the more we're willing to trust him or her.

Rituals involving sacrifice, then, function as signals of loyalty, of one's commitment to others. During these rituals, you get to see who's truly committed and who's holding back, being selfish.

Crucially, rituals of sacrifice are honest signals. An honest signal is one whose cost (to the signaller) makes it hard to fake. Which of these is a more accurate indicator that someone is a member of your group: a verbal statement of membership, or weekly attendance at group events (e.g. church)? Actions speak louder than words, and expensive actions speak the loudest.

Nominally many sacrifices are made to a god, but following Durkheim, we should note that "God" is really society writ large. When someone makes a sacrifice to your god, then, he's implicitly showing loyalty to you and everyone else who worships at the same altar.

So what do humans have to sacrifice for the sake of showing loyalty to others? In the most basic physical terms, we can offer time, resources (money, food, etc.), energy, health, status, fertility, and knowledge. Each of these is a different type of economic good (tangible vs. intangible, transferable vs. non-transferable, rivalrous vs. non-rivalrous, etc.), and so lends itself to a different type of ritual sacrifice. But no matter how it's sacrificed (or shared), watching a person give up something of value almost always makes you more likely to trust them.

Let's look at some examples:

- Food is a common object of sacrifice (or sharing), whether it's an animal sacrifice, a libation, or sharing food from a hunt or at a potluck.

- Money is sacrificed or shared through gift-giving, alms, tithing, and philanthropy. Money, however, tends to activate the technical mindset, so these acts don't strike us as particularly ritualistic.

- Health and energy are sacrificed by fasting, and in much more graphic displays by blood-brotherhood or mortification of the flesh.

- Status is sacrificed by many acts of worship, especially those involving the body — kneeling, prostrating, etc. Even the simple act of wearing a yarmulke is understood as a ritualized form of lowering one's status.

- Fertility isn't often wasted, but when it is, it's wasted in a big way, as when religious leaders take vows of celibacy, for example, or when a virgin is sacrificed. For a smaller sacrifice of fertility, see purity rings.

- Time is the easiest resource to waste, and it's sacrificed in abundance. Examples include weekly church attendance, sitting shiva, sand mandalas, and taking a road trip with friends.

But perhaps the most interesting thing we sacrifice during rituals is knowledge — a topic we turn to next.

X. Strategic ignorance

Turning a blind eye. Burying one's head in the sand. Preferring not to know the truth. All of these phrases allude to the same thing: strategic ignorance.

When the Press Secretary on The West Wing says, "I do my best work when I'm the least-informed person in the room," he's appealing to the value of strategic ignorance. When a mafia boss asks an underling to "take care of" someone, then turns and leaves before any violence takes place: strategic ignorance.

Why is ignorance ever useful? (Alternately: Why is knowledge sometimes dangerous?) It's not that ignorance itself helps us make better decisions. Rather, it's the fact that others judge us based on what we know or believe.

If it comes out that the CIA has been torturing American citizens, it's going to be a lot worse for the President if he knew about it ahead of time. If the mafia boss gets picked up by the police in connection with the murder, he gets to say with a perfectly straight face that he has no idea what happened.

But this phenomenon goes beyond merely shunning the truth to include actively believing things that are false.

"People are embraced or condemned according to their beliefs," says Pinker, "so one function of the mind may be to hold beliefs that bring the belief-holder the greatest number of allies, protectors, or disciples, rather than beliefs that are most likely to be true."

This is all well and good, but what does it have to do with rituals? To answer this, we turn to the inimitable Jonathan Haidt:

The fundamental rule of political analysis... is, follow the sacredness, and around it is a ring of motivated ignorance.

What is "sacred," according to Haidt (who takes his cue from Durkheim), is whatever is fundamentally important to the group, a matter of life or death, success or failure. And when ideas are sacred, they must be protected at all costs. The group knows where its bread is buttered, knows which ideas it needs to use to justify its most important practices — and around those ideas is where you'll find the "ring of motivated ignorance."

Strategic or motivated ignorance is the opposite of listening. It is covering one's ears. Public shouting matches. A celebration of blind faith as the cardinal virtue. And those who demonstrate the most steadfast ignorance — who clench their eyes the tightest in the face of troublesome evidence — are the best guardians of the group's sacred interests, and the most celebrated by their fellow apes.

Don't think you're off the hook simply by steering clear of faith-based religions. Every worldview has its strategic blind spots, and the deeper you're embedded in any ideology, the harder it is to see outside of it. Christians can't see the naked purposelessness of the universe, while scientific materialists have a hard time seeing the benefits of organized religion. The cult of economic growth has trouble owning up to negative externalities (whether environmental or social), while environmentalists struggle to understand the human toll of economic stagnation. Those who benefit from the status quo can't see its downsides; those who celebrate life — unquestioningly — can't think clearly about death.

If there were a single ritual to sum up all these ideas, it would be the book bonfire:

Extreme? Yes. But extremes often highlight the same tendencies that act on us all the time, lurking subliminally in the background, even in milder circumstances.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt