If any book deserves to be called a mindfuck, it's Julian Jaynes' epic, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind.

When it was first published in 1976, no one knew quite what to make of it, including some of our most intelligent critics. Daniel Dennett said, "On the face of it, [the theory] is preposterous," but also, "I take it very seriously." Richard Dawkins' ambivalence was even less reserved; he called it "either complete rubbish or a work of consummate genius, nothing in between."

Almost 40 years later, the community still hasn't reached a verdict; reactions are still all over the map. Some dismiss the theory out of hand, on the basis of its extraordinary conclusions. Others embrace it wholeheartedly, even a bit cultishly, going so far as to found the Julian Jaynes Society (after his death) to carry on his work. But by far the most common reaction is this: it's bold, it's reckless, it's probably wrong — but even still, it's worth reading.

Think about that for a second. Probably wrong — but worth reading anyway. Preposterous — but worth taking seriously. This is some strange praise. When a theory is wrong, we discard it. When preposterous, we laugh at it. What's going on here?

What makes Jaynes exempt from the usual standard of criticism is also what makes him so delightfully mind-expanding: he's asking questions that had never been asked before. Big, important questions. Questions that others have been too timid to ask. And his own answers are fantastical, yet they hover just at the edge of possibility. The dramatic tension in all of this is sublime. Reading Jaynes we find ourselves doing endless double-takes: "This can't possibly be right... can it?" Thus we admire his work not for its specific answers, but for its ability to provoke our thoughts — not for the destination, but for the journey.

Thomas Nagel once famously asked, "What is it like to be a bat?" What would it feel like, in other words, to live in a bat's body and to experience the world with a bat's mind?

As I see it, Jaynes is pursuing a similar line of questions, namely:

What type of mind did our species have just before we became fully modern? What comes between the unreflecting consciousness of an ape (or one of our ape-like ancestors) and the fully introspective consciousness of a modern human? And — here's the doozy — what if our cognitive-evolutionary path wasn't even remotely linear? What if some of our recent ancestors had a truly different type of mind?

Today and over the next few weeks, I'm going to take you on a tour of Jaynes' theory. It won't be a straightforward summary but an idiosyncratic, winding path, with plenty of detours and random stops along the way.

So hold onto your hats... it's about to get weird.

Metaphors for consciousness

Intellectual journeys often require us to wrap our heads around complex new ideas. This one is different. It requires us to get inside someone else's head — to inhabit an alien mindscape.

In order to do that, we should start with a simpler exercise: that of stepping outside our own heads for a minute. Let's see if we can stop taking our normal, everyday consciousness for granted, and learn to see it as a strange and somewhat arbitrary invention.

Note that Jaynes has a distinct way of talking about consciousness. He doesn't mean simply awareness, as most people do. He means meta-awareness — how we make sense of our own conscious experiences. How we think about our own thinking. Introspective consciousness. Most people would say that apes are conscious, for example, but as Jaynes uses the term, they aren't — only humans are conscious.

Today, here in the modern West, we use a number of metaphors to make sense of our conscious experiences. We speak of the heart, for example, as the deepest part of our consciousness, where we keep our truest, innermost feelings. We also have the gut, another cognitive organ, where we process certain emotions and make intuitive ("gut") decisions. Sometimes we even think of consciousness as a vessel, one which can be more or less 'anchored' or 'grounded' to reality, more or less prone to 'drifting off' into 'space.'

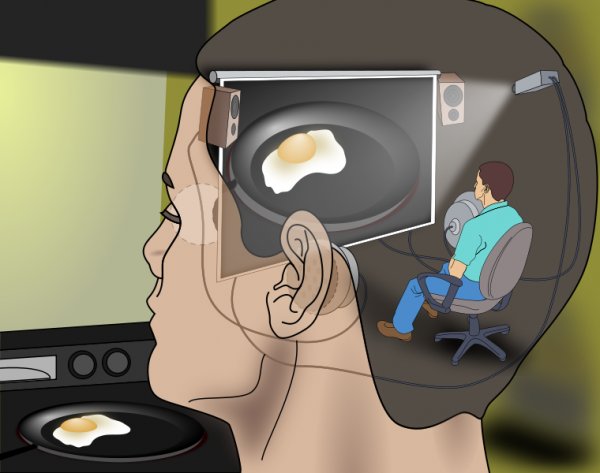

But these metaphors are weak compared to our culture's dominant metaphor for consciousness: the idea of the mind as a container, a Unified Private Headspace. According to this metaphor, consciousness (or the mind) is a 'space' inside our heads within which all of our conscious experiences take place. Each of us has our own mind-container, separate and private from everyone else's, which is the single, central, unified locus of all our mental processes: thinking, perception, motor control, decision-making, memory, language, imagination, emotions, judgments, awareness, and attention.

Dennett's idea of the Cartesian Theater, replete with homunculus, is an elaborated version of this metaphor.

This view of the mind is so dominant, in fact — so integral to our self-understanding — that we have a hard time seeing it as a metaphor. It's just what we think our minds really are, literally rather than metaphorically. This literal interpretation also enjoys the blessing of popular science, which tells us that all mental processes are the result of things happening inside our skulls, i.e., in our Unified Private Headspaces.

Don't get me wrong — this view of the mind is broadly accurate. But it's still 'just' a metaphor, just a model of reality — a construct that needs to be invented (because it isn't obvious ex ante), and which may prove to be something of a fiction.

In fact the Unified Private Headspace metaphor breaks down in a number of ways. For one, there are some very real cognitive processes that take place outside of our skulls. Emotions, for example, are partly processed in our bodies, chemically and via bodily feedback. We also have a small but separate and autonomous nervous system in our digestive tract — the enteric nervous system or "gut brain" — that can process information and affect consciousness in certain ways.

Nor is consciousness as unified as we like to believe. Many parts of our mind operate independently from each other. Some parts are in outright conflict with others, or conspire to hide things from each other. A lot of decision-making seems to happen unconsciously, and we only rationalize it later as having taken place 'in' consciousness. Etc.

Finally, consciousness isn't necessarily a private affair. In fact, our 'private' 'inner' mental states leak out through our faces and bodies all the time, and it's only by specific acts of will that we're able to keep them private — and even then we often fail at it. A person who's especially gifted at deciphering nonverbals will appear to others as capable of mind-reading, for example. Emotions in particular are hard to keep private; wearing them on our sleeves seems to be the default.

My point is that this idea of the mind — as a Unified Private Headspace — isn't obvious (or wholly accurate) even from the perspective of modern science. And it certainly wouldn't have been obvious to our ancestors, some of whom thought the brain was an organ for cooling blood. Yes, in the West we can take this metaphor for granted, since it's monopolized how we talk and think about consciousness for at least 2500 years. But it's something that had to be invented — and thus there was a time, before its invention, when the human mind conceptualized itself very differently.

We even have a record of this pre-modern mentality. It just takes some care to decipher properly.

Language as a window into the mind

We all understand the process of translating a text. The translator, someone familiar with both languages, simply has to find the best mapping from the source text into the words and phrases of the target language. This is relatively simple for concrete concepts, but gets progressively more difficult as the concepts get more and more abstract. Physical concepts are easy to translate — a tree is a tree, and has been for as long as humans have been around to talk about them. Cultural concepts are a bit harder, since the source and target cultures may not be perfectly analogous. But if Jaynes is right, mental concepts are the hardest of all, in part because they're so abstract and nebulous, but also because we don't appreciate how much they can vary between cultures and change over time.

It's in this spirit, aware of these dangers, that Jaynes invites us to consider the Iliad. Most translators assume that the ancient Greeks had the same mentality that we have today, with roughly the same concepts for introspecting and expressing mental concepts. But Jaynes says we can't take this for granted, and I think he's right. So what happens when we abandon that assumption?

I don't know ancient languages so I can't double-check Jaynes on this one. But he makes a fascinating case, one that sounds very plausible to my ears. As he sees it, the Greeks only developed a modern mentality around 600 B.C. Before that time, e.g. in the Iliad (~1200 to ~900 B.C.), they had very different mental concepts. The earlier Greeks may have used the same words as the later Greeks, but the earlier meanings were much more literal.

The Iliad, as seen by Jaynes, portrays a folk-theory-of-mind that's fragmented into a variety of different cognitive 'organs' and localized in different parts of the body.

One of these organs, for example, was the phren (or plural, phrenes), which referred originally to the lungs or the breath. What cognitive process took place 'in' the phrenes? A: Being surprised by something, or having a surprise realization. You can try it yourself. Look across the room, pretend you've seen something shocking, and breathe in sharply. From this you can imagine how the Greeks might have considered surprise to take place 'in' the breath.

Another ancient Greek cognitive organ was the noos (or nous), referring originally to sight or the eyes. 'Seeing things' obviously makes sense as a function of the noos, but by metaphorical extension, so does perception (a kind of abstract 'seeing'), and perhaps memory and imagination as well. We still speak of an organ like this, on occasion, as "the mind's eye." But although the Greek's noos was localized in the head, it was not a general-purpose cognitive organ. Very important functions like judgment and decision-making, for example, can't take place in the noos, even metaphorically, just as today your mind's eye can't 'decide' to do something.

Yet another cognitive organ was the thumos, localized sometimes in the chest, which was a decision-making organ (of sorts) capable of initiating action, especially on the basis of emotions. Gods would sometimes "cast strength" in a person's thumos, which would rouse him to action. Often a warrior would consult his thumos to see if he was ready to fight.

Finally there's psyche, the word that would later come to mean 'soul' or 'mind' as we think of it today, and from which we derive "psychology," the study of mind. But in the Iliad, psyche referred not to a cognitive structure at all, but rather to a "life substance" akin to blood or breath. A warrior, for example, bleeds his psyche out onto the ground.

What these examples illustrate is that, during the Iliadic period, all the Greek words for mental concepts had concrete meanings, and most were associated with specific parts of the body. But by the time of Socrates in ~500 B.C., many of them (phren, noos, and psyche in particular) had coalesced in meaning, so that they all came to refer to the modern concept of the 'soul' or 'mind.' Thus did the Greeks slowly and gradually develop their notion of a Unified Private Headspace, a notion that's still with us to this day, part of Western civilization's classical inheritance.

The birth of dualism

This blew me away when I read it: According to Jaynes, the ancient Greeks had no word for 'body.'

Yes, the more modern Greeks had soma, which we still use today, e.g., when referring to 'somatic' cell lines or 'psychosomatic' illnesses. But in the Iliad, soma referred only to a dead body, that is, to a corpse. Of course the Iliadic Greeks had words for all the different parts of the body, but no word to refer to the entire thing.

This is very illuminating. Without the notion of a single unified 'mind', there's simply no demand in the language for a word that refers to the body. A man simply was his body. It would be redundant to say that Achilles' body was tired. Achilles and his body are synonymous, and he is tired — period, end of story. I don't need to say "My body is covered in paint," when I could simply say, "I'm covered in paint."

It's the same way we almost never talk about the 'bodies' of our pets. It sounds strange to say, "Fido's body is tired," because we don't typically think about a dog as having a mind separate from and independent of its body. Fido is just one big, continuous, organic process.

I must confess that this is very appealing to me, this equation of animal with its body (whether dog or human). I'm a materialist, metaphysically speaking. I don't think there's a 'mental' realm separate from the physical realm — it's physical all the way down. It can be useful, on rare and special occasions, to differentiate mind and matter, e.g. when discussing philosophy of mind. But in everyday life, for practical purposes, mind and matter are one and the same. We are "thinking meat," to borrow the uncanny phrase from Terry Bisson's short story. "The meat is the whole deal."

What Jaynes is arguing here is that the human animal begins from a position of naive (unconsidered) monism, and that dualism — the separation of soul from substance, mind from matter — is something that needs to be invented or assembled by some cultural process. Further, we can date this invention by when people start referring to their bodies. In the case of the Greeks, Jaynes dates it to the 6th century B.C., and describes it like this:

[W]ith this wrenching of psyche = life over to psyche = soul, there came other changes to balance it as the enormous inner tensions of a lexicon always do. The word soma had meant corpse or deadness, the opposite of psyche as livingness. So now, as psyche becomes soul, so soma remains as its opposite, becoming body. And dualism, the supposed separation of soul and body, has begun....

Cults spring up about this new wonder-provoking division between psyche and soma. It both excites and seems to explain the new conscious experience, thus reinforcing its very existence.... It becomes an object of wide-eyed controversy.

I can only imagine the spiritual intoxication that would have led to these cults. The Greeks were opening up an introspective 'space' in their minds and developing some powerful abstractions to explain it. Thanks to those early psychic architects, the entirety of Western civilization is now irreducibly dualist. The idea of mind-separate-from-matter is embedded in our language, our culture, and our introspective consciousness.

But this wasn't always the case, and if we're serious about understanding the ancient mind — what it was like to experience the world as a human living in 2000 B.C. — we need to learn to see the world non-dualistically.

Such a project would have other merits as well — like seeing the world for what it really is. There's something to be said for the naiveté of early humans who weren't yet capable of reifying their abstractions. A lot of my own writing, in fact, has been an attempt to reinstate just this kind of materialist attitude toward the world, intellectually and spiritually.

We aren't Cartesian souls imprisoned in lumbering robot bodies, exchanging thought-packets with other souls by shouting across the dead, mindless space between us. We are animals, synonymous (for now) with our bodies — organic expressions of the natural world with boundaries more porous than we care to admit.

There's a wonderful story to tell about how we evolved, from dust, to become what we are today. Jaynes' contribution is to have written the first draft of a new chapter of that story — about how we became not just thinking meat, but introspective meat.

_____

This was the first installment of a four-part series:

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt