To reject gods and spirits is easy: just bully them away in the name of science.

But to accept them, or at least our experiences of them, and yet give them a scientific explanation: there's a task worthy of our art. It demands that we look them in the eye and take them seriously, while standing absolutely firm in our materialist convictions.

I don't know how much of what I'm about to say is true. All I know is that it's damn interesting.

Today we court madness from the bedrock of science. Today we will face addictions and compulsions, alter-egos and imaginary friends, angelic voices and demonic possessions, even exorcisms. And we will attempt to ground these madnesses, one and all, in a unified, sane, materialist framework.

We will begin, naturally, with the neuron.

Neurons, selfish and feral

In a recent Edge interview, Dan Dennett pitches the most fascinating new idea I've read in a long, long time: That our neurons are powerful computational building blocks in part because they've reverted to an older and slightly feral state.

Here's Dennett [1]:

Realize that every human cell in your body, including your neurons, is a direct descendent of eukaryotic cells that lived and fended for themselves, for about a billion years, as free-swimming, free-living little agents. They had to develop an awful lot of know-how and self-protective talent to do that. But when they joined forces to become multi-cellular creatures, they gave up a lot of that. They became, in effect, domesticated — part of larger, more monolithic organizations.

In general, we don't have to worry about our muscle cells rebelling against us. (When they do, we call it cancer.) But in the brain, I think, some little switch has been thrown in the genetics that, in effect, makes our neurons a little bit feral. It's like what happens when you let sheep or pigs go feral: they recover their wild talents very fast.

Maybe the neurons in our brains are not just capable, but motivated, to be more adventurous, exploratory, or risky in the way they live their lives. They're struggling amongst themselves for influence and for staying alive. As soon as that happens, you have room for cooperation, to create alliances, coalitions, cabals, etc.

Dennett traces this idea — of the "selfish" neuron — to computational neuroscientist Sebastian Seung. According to Seung and Dennett, it's precisely because of neuronal selfishness that the brain is able to "spontaneously reorganize itself in response to trauma or novel experiences." For example:

Mike Merzenich sutured a monkey's fingers together so that it didn't need as much cortex to represent two separate individual digits, and pretty soon the cortical regions that were representing those two digits shrank, making that part of the cortex available to use for other things. When the sutures were removed, the cortical regions soon resumed pretty much their earlier dimensions.

Or if you blindfold yourself for eight weeks, as Alvaro Pascual-Leone does in his experiments, you find that your visual cortex starts getting adapted for Braille, for haptic perception, for touch.

Why should these [idle] neurons be so eager to pitch in? Well, they're out of work. They're unemployed, and if you're unemployed, you're not getting your neuromodulators, so your receptors are going to start disappearing, and pretty soon you're going to be really out of work, and then you're going to die.

In other words, the selfishness of neurons incentivizes them to be useful — to hook up with the right network of their fellow neurons, which is itself hooked up with other networks (both 'up' and 'downstream'), all so they can keep earning their share of life-sustaining energy and raw materials.

Thus there is, in this view, an internal 'economy' in the brain, in which neurons must compete with each other for resources. This design stands in contrast to the standard, Von Neumann computer architecture, whose parts never have to worry about where their energy is coming from. Without resource contention, there's no need for selfishness. And this is, in part, why computers are less flexible and adaptable — less plastic — than brains.

Plasticity, says Dennett,

is itself one of the most amazing features of the brain, and if you don't have an architecture that can explain it, your model has a major defect. I think you really have to think of individual neurons as micro-agents, and ask what's in it for them?

Neurons as agents: This could well be the single most important fact about our brains.

Agents all the way down

So what is agency, exactly, and why is it so important?

For our purposes, an agent is an entity capable of autonomous, intelligent, goal-directed behavior.

People are agents, clearly. So are corporations and governments, insofar as they pursue goals (like 'maximizing shareholder value' or 'defending territory'). Even a plant can be said to have agency, since it 'wants' to grow toward the sun. Not all agents need to be selfish — e.g., a non-profit — but any system that can be called selfish (like a neuron) will necessarily be an agent.

But agency isn't binary; it's not something you either 'have' or 'don't have.' Instead it admits of degrees. The more autonomous, intelligent, adaptive, and purposeful a system is, the more agency we will attribute to it. Thus children tend to have less agency than their (more intelligent, purposeful) parents, and slaves less agency than their (more autonomous) masters.

Another key fact is that agency isn't intrinsic to a system, but rather something we ascribe to it. It's a way of describing a system at the level of abstraction that includes goals, obstacles, motivations, etc. If you look too closely (at a sufficiently low level of abstraction), the agency might seem to disappear. A plant, for example, is 'merely' growing its stem according to the concentration of auxin, just like we (humans) are often 'merely' acting on our drives and instincts. But zoom back out, and once again it will be productive to describe the system at the agent-level of abstraction. Thus explanatory power, not free will, is the hallmark of agency.

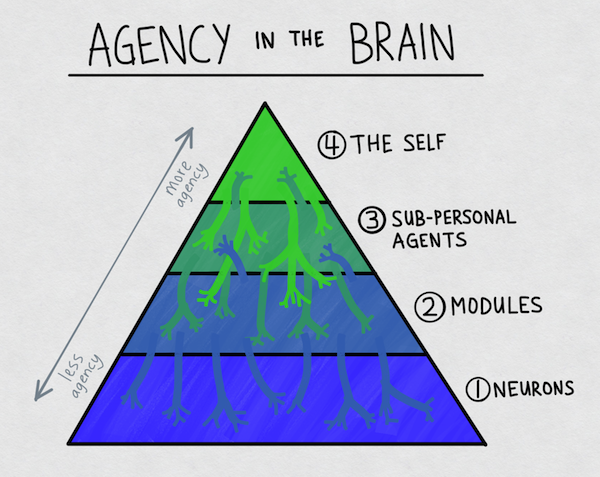

The questions I want to investigate today concern the agency of different systems in the brain. We can line these up in a pyramid, with a single agent at the top built on other agents all the way down:

Of course there's no strict delineation between these different "levels." They're just convenient labels for us to talk and reason about them. In reality the brain is a tangled mess of agents operating on many different levels, often simultaneously; in Hofstadter's phrase, it's a heterarchy rather than a hierarchy.

What I'm going to argue today is that agency is a fundamental property of the brain. Not only is agency the function of the brain — and thus it's very reason for existence — but it's also built into the brain's fabric and architecture. Because even neurons have agency, in the form of (metabolic) selfishness, higher-order brain systems don't need to create agency 'from scratch' out of mindless robotic slaves. They inherit agency pretty much for free.

The brain is thus uniquely hospitable to agents, who can be said to take root and grow in the brain quite readily.

There's actually a more general principle here, namely, that rich substrates are more fertile, more conducive to growth. Bacteria grow better in glucose-rich agar than in saltwater. Plants grow better in (organic) soil than in (inorganic) sand. Ideas grow more quickly in a highly-connected society than in a sparse one. And so on.

Similarly, agents grow best on a substrate rich in agency. Computers, though technically capable of supporting agency, aren't particularly hospitable to it. The brain, in contrast, is already teeming with agency (in the form of billions of selfish neurons), and is thus uniquely fertile.

Hang on to the organic growth metaphor. It's important, and we'll come back to it soon.

In the meantime, let's see how agency plays out at the different levels of the brain. We'll work our way up from the bottom, having already covered level 1 (neurons).

Level 2: Modules

Modular views of the mind date back to the early days of AI. In 1959, Oliver Selfridge proposed a 'Pandemonium' architecture for an AI system, full of little independent 'demons' that had simple, goal-oriented jobs. Dennett also refers to his modules as 'demons' in Consciousness Explained, following Selfridge. In The Society of Mind, Minsky refers to them simply as 'agents.'

The basic idea is that there's a level of abstraction where we can describe the brain in terms of hundreds, thousands, or even millions of little modules, more or less independent of each other, each with its own functional purpose or goal. These modules have agency, of course, but are fairly limited in scope. Examples include edge detectors (in the visual system), finger controllers (in the sensorimotor cortex), and verb conjugators (in the language system).

Modules are covered pretty extensively in the literature, so I won't belabor the idea. I'll just point out that, if Dennett and Seung are right, modules inherit some of the same type of agency — i.e., selfishness — as the neurons out of which they're built. There's a real sense in which a module 'wants' to keep it's 'job', because when it's out of work its neurons wither away. Sometimes these unemployed modules can be quite clever about taking on new jobs, as when the visual system gets repurposed for Braille.

Level 3: Sub-personal agents

At the level above simple modules, but below the self, are poised what I will call sub-personal agents. These are systems like drives or instincts — hunger, lust, curiosity, greed, addictions — that have agency recognizable even to lay-people. We don't need neuroscience to reason about these agents because we can 'feel' them, through introspection, pulling at our psyches — faintly or insistently, gently or violently. And indeed, people have been reasoning about these systems, as agents, for thousands of years.

Sub-personal agents aren't capable of using language directly (like the self is), so their agency is limited and less outward-facing. But they nevertheless have real power, in that they're capable of influencing the cognition, emotions, and behavior of the human creatures they inhabit. They're also capable of co-opting the reasoning process to justify their desires.

Sub-personal agents also have immense explanatory power. This is most visible in the life of an addict. The addict 'himself' often doesn't want to keep up the addiction, but he keeps doing it anyway. Thus the addict is often described, even by himself, as powerless, and perhaps the best, most parsimonious explanation for his behavior is that there's literally another agent inside his brain — his inner addict — realized as a particular cabal of neurons and modules.

When you take an addictive drug for the first time — nicotine, let's say — a new agent begins to bud around that source of pleasure (i.e., the neurotransmitters that flood your brain while smoking). The agent starts out small and weak. But the more you feed it, the bigger it grows, until there are many neurons, many modules, and even other brain-agents under its influence, feeding off the nicotine and craving it in ever larger doses, co-opting your planning and reasoning skills so it can scheme about how to get more of it.

This process, of course, is extremely adaptive for us, as evolved organisms — but only when the pleasure corresponds to something of survival or reproductive value: food, sex, social status, mastery of physical skills. The fact that our brains are capable of growing agents dedicated to pursuing food and sex is essential to our survival. It's only in the modern (super-stimulating) environment that we get into trouble.

This American Life did a nice segment on addiction a few years back, in which the producers — seemingly on a lark — asked people to personify their addictions. "It was like people had been waiting all their lives for somebody to ask them this question," said the producers, and they gushed forth with descriptions of the 'voice' of their inner addict:

"The voice is irresistible, always. I'm in the thrall of that voice."

"Totally out of control. It's got this life of its own, and I can't tame it anymore."

"I actually have a name for the voice. I call it Stan. Stan is the guy who tells me to have the extra glass of wine. Stan is the guy who tells me to smoke."

Note that this isn't literal speech, as in an auditory hallucination. Instead, the 'voice' is simply an agent whose influence is accessible to introspection, and thus capable of being put to words, as an imaginative/interpretive gloss. That we call them voices is simply a testament to the high level of abstraction at which these agents operate.

It's this same sense — abstract, non-explicit — in which these agents engage in 'reasoning,' 'negotiation,' 'bargaining,' joining 'alliances,' and other forms of coalitional politics. When two sub-personal agents are bargaining, for example, they're not using words to do it, but the process is nevertheless the kind of thing that can be put into words — and thus these agents can be very 'persuasive'. Again here's This American Life:

[Over-sleeper] "Then I'll get up five minutes later and [the voice will] be like, 'Eh, I mean, you don't need to iron a skirt. Do you really need to iron the skirt? If you need to iron the skirt, do you need to be wearing the skirt? Maybe you could wear a different skirt, and then you could sleep for 10 more minutes.' And that seems like a reasonable negotiation."

Obsessions, compulsions, addictions, and other "inner demons" aren't the only agents with real power to control and explain our behavior; our brains are host to 'benevolent' agents as well. Our consciences, for example. These are agents that live inside our brains, who are being trained throughout our lives, but especially in childhood, by our interactions with parents, authority figures, and other moral teachers, and by various rewards and (especially) punishments.

Certain religious communities, such as the evangelicals studied by Tanya Luhrmann, spend a great deal of time and effort teaching themselves to 'hear' the (metaphorical) voice of God, or to interpret His will. "People train the mind," she says, "in such a way that they experience part of their mind as the presence of God." This 'God' is nothing more and nothing less than an internalized, personified agent representing society's interests.

It's an interesting feature of our brains that society (or perhaps "elite society") can install these types of agents — God, the conscience, a sense of morality — to look after its own interests. This is reminiscent of the way the UN will install weapons inspectors or election observers inside otherwise-sovereign nations.

Level 4: The self

Finally we come to the self — I, ego, myself, my conscious will.

By now I hope I've shown that the self isn't the only meaningful agent in the brain. But it is the dominant agent, or at least the one in a position of nominal leadership. Mike Travers gives this memorable description of the self (emphasis mine):

A person, like a society, is composed of parts with their own private agendas, all taking part in a continuously renegotiated dance of conflict, cooperation, and compromise. Our disparate motivations are like politicians trying to advance a faction, and the self, such as it is, is something like a prime minister — not powerful in its own right, but because it has managed to become the public face for the most powerful faction.

In this view, the self is a social agent. It's both externally- and internally-facing, its role as much public relations as executive control.

Now this is what I find especially profound. If we accept that the brain is teeming with agency, and thus uniquely hospitable to it, then we can model the self as something that emerges naturally in the course of the brain's interactions with the world.

In other words, the self may be less of a feature of our brains (planned or designed by our genes), and more of a growth. Every normal human brain placed in the right environment — with sufficient autonomy and potential for social interaction — will grow a self-agent. But if the brain or environment is abnormal or wrong (somehow) or simply different, the self may not turn out as expected.

Imagine a girl raised from infancy in the complete absence of socializing/civilizing contact with other people. The resulting adult will almost certainly have a self concept, e.g., will be able to recognize herself in the mirror. But without language, norms, shame, and social punishment, the agent(s) at the top of her brain hierarchy will certainly not serve a social/PR role. She'll have no 'face', no persona. She'll be an intelligent creature, yes, but not a person.

In this way, the self takes on a structure that depends on (and reflects) the environment it's raised in.

'Birth defects' in the self

Now if the self is the result of an organic growth process, then perhaps it makes some of the same mistakes as other, similar processes.

Life, as I've pointed out before, is capable of some pretty bizarre and amazing things. Case in point:

This is the condition known as polycephaly or multi-headedness. It's just one of the many birth defects involving supernumerary body parts, which also include fingers (polydactyly), limbs (polymelia), and yes, even penises (polyphallia).

How does this happen? How can an animal end up with two heads or three arms?

The mechanism is actually quite simple — and quite illuminating. As we know, every zygote (sperm + egg) must turn into a many-trillion-celled animal by replicating itself. But in doing so it must simultaneously differentiate into various 'cell lines' destined to produce each of the different tissues, organs, and appendages — arms, legs, eyes, spleens, lungs, arteries, skin, etc., etc.

Now if a replication error or conjoined-twin scenario creates two 'head' cell lines instead of just one, the embryo will simply develop two heads(!). The point is that the developing embryo is capable of growing all sorts of tissues/appendages/organs in a variety of locations. It's merely the careful regulation of the number and location of these cell lines which ensures that we are almost always single-headed, two-armed, etc. But the potential for growing all sorts of things is there, in the embryo, just waiting to be tapped by the right (or wrong) arrangement of early cells.

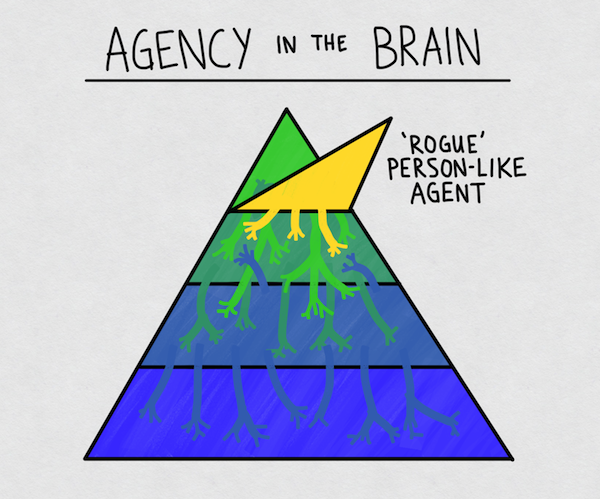

I contend that something similar can happen to agents growing in the brain: that it's possible for the self to develop 'birth defects' during the process of self-formation (which occurs long after biological birth, of course).

As we've seen, the brain is uniquely hospitable to agency (just as an embryo is hospitable to tissue and organ growth). Most normal human brains, in normal environments, will naturally grow a single agent (the self) at the top of their agent hierarchy. But what if the brain or the environment isn't quite normal? Are we capable of growing other selves or person-like agents — even multiple ones in a single brain?

The answer, I think, is yes.

Multiple occupancy

So: what kind of 'rogue' agents are capable of taking root and growing in our brains, alongside our selves?

It turns out there are a few different types.

In schizophrenia, the patient can hallucinate one or more separate voices, each with its own motives, personality, etc. But hallucinated voices aren't unique to schizophrenia and don't necessarily entail psychosis. Voices run the gamut from persecutory to helpful, and can even become indispensable. Joan of Arc heard a few different voices which helped her to "govern" herself. "Whatever I have done that was good," she said, "I have done at the bidding of my voices." William Blake saw visions throughout his life, and composed large parts of Milton "without Premeditation & even against my will." Socrates, of course, was attended by his personal daimonion.

In dissociative identity disorder (previously known as multiple personality disorder), two or more person-like agents inhabit the same brain. These cases are rare, and may be induced during therapy (iatrogenetically) rather than arising spontaneously in response to trauma. In any case, they probably don't involve wholly separate agents, but merely different, non-memory-sharing 'states' or facets of the same agent.

During a possession trance, a 'spirit' agent takes over and assumes control over the body, voice, etc. Clearly there are no non-material entities involved here — but we can't let someone else's bogus explanations mislead us into thinking the phenomenon itself isn't real. I discussed possessions (and hallucinations) in detail last time; Johnstone explores them at length in Impro. "One would expect the gods [spirits] to be presented as supermen," he says, "But in all 'trance' cultures we find a mythology which describes the gods as acting in a childlike way.... The gods are like children and must be told what to do." They must even be taught how to speak, starting first in gibberish until they learn the proper words for things. This sounds much more like a new brain-agent in need of training, rather than an intentional act put on by a fully-conscious, single-minded person.

Additionally, in split-brain patients, the brain is divided into left and right hemispheres, each then becoming a distinct agent. Though only the left hemisphere is capable of speaking, both hemispheres can comprehend language, and both can control their respective halves of the body and initiate stereotyped motor sequences (like walking). But they can't share information. In one famous experiment, a command was presented to the patient's right hemisphere: "Get up and walk toward the door." When asked what was going on, the left hemisphere (who had no idea) made up a reason on the spot: "I'm going out to get a coke."

Each of these different types of agents — hallucinated voices, alter egos, possession spirits, split hemispheres — has a different 'wiring diagram.' Each commandeers verbal faculties, reasoning faculties, and control of the body in different ways. Each has a different set of triggers for being summoned and/or appearing unbidden.

But what's common to all of these phenomena is that they seem to involve separate entities — agents who aren't wholly 'us' — living inside our brains. God knows, they may even be sentient. There's certainly nothing in principle that would prevent a brain from hosting two separate sentient creatures. And while I can't say for sure that it's true, the mere possibility of it should give us pause.

Agent horticulture

I don't know why I was surprised.

It turns out there's a community — on the internet (where else?) — trying to intentionally cultivate these kinds of agents in their brains.

Unlike other communities with a similar goal, this one is fully grounded in physical reality. They admit no woo-woo spiritual nonsense to their discussions or explanations; their effort is fully compatible with a materialist understanding of the world.

The agents they're trying to cultivate are called tulpas. From the FAQ:

A tulpa could be described as an imaginary friend that has its own thoughts and emotions, and that you can interact with. You could think of them as hallucinations that can think and act on their own.

Alternately, from tulpa.info:

A tulpa is believed to be an autonomous consciousness, existing parallel to the creator’s consciousness inside the same brain, often with a form (mental body) of its own. A tulpa is entirely sentient and in control of their opinions, feelings, form and movement. They are willingly created by people via a number of techniques.

Six months ago I would have brushed this off as childish fancy, but now I'm not so sure. I can't tell you with any degree of certainty whether tulpas are real or not, but the material produced by this community reads like a good-faith, practice-oriented, engineering effort to grow and train a new brain habit. Their practices are entirely consistent with the idea of agency-inherited-from-selfish-neurons. For example, to grow a tulpa, you have to spend many, many hours (on the order of 100) imagining it, thinking about it, talking to it, and visualizing it — in other words, feeding it with attention. Or here's the FAQ on how to get rid of one:

Q: How do I permanently get rid of a tulpa?

A: Ignore them and deny them attention until they entirely dissipate. This is not a pleasant experience for a tulpa, and if you have developed them for any length of time it may well be emotionally draining on you too. It is not a quick or easy process.

Which sounds a lot like trying to kick an addiction.

Here's the bottom line. If biology can grow this:

Or this:

Or these two:

Then maybe it's not so strange to think our brains are capable of growing a tulpa.

Taking demons seriously

One final thought — on making sense of exorcism.

If an exorcist explains his work in terms of spirits that live outside the body, then he is quite simply mistaken. "What delusions!" we think. "Doesn't he know science?"

But let's be careful here; it's too easy to get smug and self-righteous about this. If we simply walk away, we're leaving unanswered questions on the table. Science isn't (just) about discrediting bad explanations. It's also about providing good ones. And when it comes to things that smack of the "paranormal," we too often get caught up in the refutations, forgetting that there are real phenomena in need of explanation.

Sure there are charlatans, and I'm not saying we should take alien abduction stories seriously. But a practice like exorcism — one that's been around for all of recorded history, in most parts of the world and in almost all religious traditions — demands at the very least an anthropological explanation. Why do so many cultures practice exorcism? What, exactly, is going on?

I'm sure you can guess where I'm going with this. I suggest we try to be charitable and give the exorcists some credit. When they say they're casting out demons or evil spirits, what if we understood that to mean that they're casting out brain-agents?

In fact we can say this:

Exorcism is a form of psychological therapy in which the disease is treated as an agent.

In other words, an exorcist is a healer who takes the intentional stance toward a person's inner demons. Instead of looking for a medicinal cure (physical stance), and instead of addressing the patient's 'self' (psychological stance), the exorcist addresses the patient's ailment directly. This could entail any number of things: negotiating with it, reasoning with it, bribing it, showing it love and compassion, making it swear an oath, threatening it, or commanding it in the name of a higher power.

When you start to look at exorcism this way, you can see how it might be effective — at least for a certain class of ailments under certain conditions. Something along these lines seems to have worked for Eleanor Longden's schizophrenia, for example, as she explains in this TED talk.

In most cases, the exorcist must be a high-status authority figure for many of these techniques to be effective. In fact, they might work simply by convincing the self-agent that it has a powerful ally — the shaman/priest/God — in its internal battles with the disease-agent.

Clearly exorcism won't cure all diseases or even all psychological issues. And in scientifically backward cultures it will certainly be applied to diseases it has no hope of curing (e.g. Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome). But unlike most modern drugs, exorcism has no major side effects. And if it cures or ameliorates 1 in 10 cases, well, maybe that's enough for the practice to stick around and catch on.

Next week

Next week we'll return to Julian Jaynes and his weird, wild theory which, after today, might not seem so weird at all.

_____

This was the third part in a four-part series:

Further reading:

- Patterns of Refactored Agency [Mike Travers at ribbonfarm.com] — sublimely thought-provoking.

- The Government Within [Mike Travers at ribbonfarm.com]

- The Normal Well-Tempered Mind [Dan Dennett at edge.org]

[1] I've pared down Dennett's remarks (from an extemporaneous interview) and edited them slightly, to better suit this medium. You can read the full transcript here.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt