You probably know someone like this:

Daniel is a 25-year-old software engineer described by his friends as someone who "likes to have things his own way."

Food: he's picky and sticks to what he knows. Clothes: he wears the same type of outfit every day (the style he adopted in college). Plans: he likes to make them and stick to them, and gets anxious when they change at the last minute. Routine? Yes please!

In short, his comfort zone is narrow.

He also sets a strict code of conduct for himself. He's a man of principles and takes pride in resisting peer pressure. Whether his principles are ethical or aesthetic, he cleaves to them with equal rigor, often at great personal inconvenience. He also prides himself on being immune to the "herd mentality." He likes to think for himself, and he maintains a strong, consistent set of beliefs which he will defend to the death.

That Daniel is an engineer is no coincidence. He relishes imposing regularity on an all-too-messy world. He's also an atheist and a libertarian — or at any rate, allergic to authority in all guises.

Above all, Daniel is true to himself.

I know a lot of Daniels. It's an occupational hazard — or perk (take your pick).

Today we're going to dig into Daniel's approach to personal identity. How does he understand his identity and his behavior in relation to it? What does it mean for him to be true to himself, or conversely, to betray himself?

To get started, let's turn to drugs.

Drugs and alcohol

By now I'm sure you've guessed: Daniel's a bit of a teetotaler. He won't touch recreational drugs (hard or soft), and if he drinks at all, he stops well short of full-on drunk.

This isn't a moral imperative or a fear of breaking the law. He's libertarian enough to appreciate that how people treat their brains and bodies is their own business, as long as they do it responsibly and consensually. Neither is it a fear of "frying his brain" or "putting holes in it." He's well versed in the literature and knows that some drugs are extremely safe (safer than alcohol, as he's quick to point out). In fact he's wary of any kind of "altered consciousness," even those that aren't chemically-induced — e.g. hypnosis, trance, religious ecstasy, and all manner of collective effervescences.

No, his fear comes from a different place. Drugs and alcohol scare him because they threaten his sense of personal identity.

This isn't a metaphysical concern. He knows that whatever substances he consumes — or whichever rituals he participates in — he'll remain the same person: the same lump of grey jello, tingling with energy inside his skull.

It is, rather, an aesthetic concern. He's worried that he'll end up behaving in ways that don't feel right. That altered consciousness will up-end his sense of self and do irrevocable damage to his identity.

In a way, he's right.

Prickles and goo

As armchair psychologists, we might 'diagnose' Daniel with something like Asperger's — and he would likely agree. But the philosopher Alan Watts prefers to call him prickly.

Here's Watts contrasting "prickly" people with "gooey" people:

The prickly people are tough-minded, rigorous, and precise, and like to stress differences and divisions between things.... The gooey people are tender-minded romanticists who love wide generalizations and grand syntheses.... Prickly philosophers consider the gooey ones rather disgusting — undisciplined, vague dreamers who slide over hard facts like an intellectual slime which threatens to engulf the whole universe in an "undifferentiated aesthetic continuum".... But gooey philosophers think of their prickly colleagues as animated skeletons that rattle and click without any flesh or vital juices, as dry and dessicated mechanisms bereft of all finer feelings.

But it's not just whole persons who are prickly or gooey. All of us have our prickly parts and our gooey parts. The questions to ask are Which parts? and What's the ratio of prickles to goo?

We could also call these the hard and soft parts of our identities. The hard/prickly parts are uncompromising and unyielding. They feel necessary and essential. They are exclusive; they define boundaries with a privileged 'inside' and an excluded 'outside.' If your tastes in music are hard or prickly, you'll feel good about excluding certain genres and artists from your identity.

In contrast, the soft/gooey parts of identity are open to influence from others. They represent possibilities, potentialities. They are inclusive. If your musical tastes are soft, you'll feel bad about your inability to appreciate certain genres/artists, and you'll strive to be more open-minded. (The word "open" here suggests that this is basically the O in the OCEAN five-factor model of personality, FWIW.)

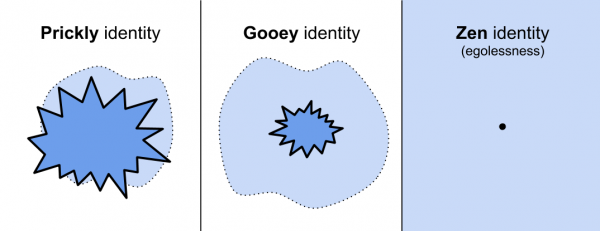

It should be clear, then, that Daniel is a prickly fellow. But the problem isn't that he's all prickles and no goo — everyone has both parts, even Daniel (though he's pricklier than most). No, the problem is that he identifies only with his prickly parts. This is the central aesthetic choice that defines so much of his identity: the choice to define himself in opposition and by exclusion, rather than with possibilities and by inclusion.

This choice enables Daniel to maintain a very strong sense of himself. But it comes at a cost.

Zen and the math of personal identity

Buddhism — especially the Zen variety — offers no end of puzzles for analytically-minded folks to cock their heads at. But for me, the most intriguing are the teachings about personal identity, and especially about the size of the self.

Consider these two contradictory ideas. On the one hand, Buddhism invites us to have a smaller self:

In the early texts, the Buddha [taught] that all things perceived by the senses (including the mental sense) are not really "I" or "mine," and for this reason one should not cling to them. (Wikipedia)

But the result of having a smaller self is that... you feel larger!

The more you become aware... the more you realize that [the self] is inseparably connected with everything else that is... That vast thing that you see far, far off with great telescopes... you look and look, and one day you're going to wake up and say, "Why, that's me!" (Alan Watts)

I'm sure all of this is clarified in some fundamental text. But I'm an amateur here, so I've had to come up with my own interpretation — and I think I've finally unlocked it.

Let's put on our math hats for a minute. Consider this piece of notation:

{ state : ∀c ∈ {conditions} state satisfies c }

English translation: The set of all states that satisfy {conditions}.

There's a 'self' in here, but the important question is: where? Is it in the conditions or in the states?

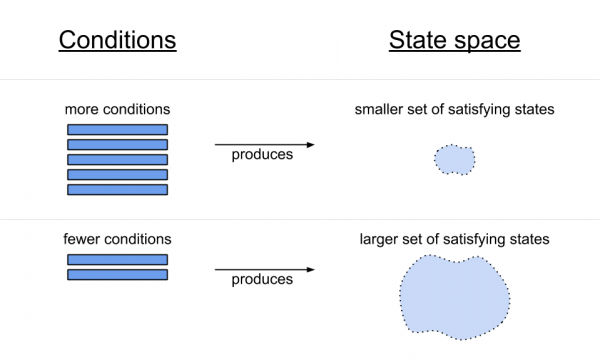

The answer, of course, is both — because they're two sides of the same coin. It's an inverse relationship: the more you qualify your identity with conditions, the fewer states you'll identify with. And vice versa: if you impose fewer conditions on your identity, you'll end up with more states that satisfy those conditions. For example, if you identify with only those moments of existence when you feel in conscious control of your thoughts and actions, then you'll exclude states like sleep, trances, drunkenness, etc.

Here it is in the form of a diagram:

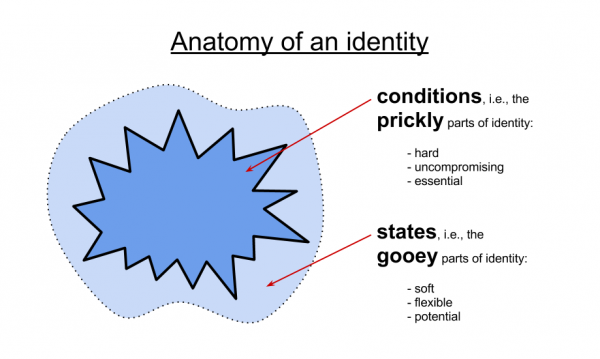

We can make these identity diagrams more evocative (if slightly less precise) by drawing the conditions on top of the states and rendering them more "prickly":

This is how we resolve the apparent contradiction in the Zen approach to personal identity. In some treatments, "the self" refers to the conditions; in others, it refers to the states. When you distinguish these two senses of "the self," Zen becomes very consistent — it argues for a smaller set of conditions and a larger set of states.

You can even take this to the limit (as Zen practitioners strive to do). If you shrink the prickly, condition-based self to nothing, the gooey, state-based self expands to include everything in existence:

Daniel thinks this is patent nonsense, of course. He sees no value in having a smaller (prickly) self, because he doesn't identify with his gooey side.

Drugs and identity

I think we can now appreciate why Daniel is afraid of drugs and states of altered consciousness.

A quick note on "consciousness." We're concerned here with those aspects of consciousness that vary between people and, for a given person, across different times and moods. We're not talking about (capital-C) Consciousness, i.e., what separates us from rocks and machines, but rather the more mundane (lowercase-c) consciousness, of which there are many varieties. For our purposes, we're going to treat consciousness as a particular pattern of attention and control — how we pay attention to the world, and what kinds of control we feel over our behavior.

Now Daniel has spent his entire life operating within a given, relatively narrow range of conscious experience — and he defines his identity to privilege that range. It's the hallmark of a prickly person that he likes to feel in control (of both his attention and his behavior) at all times.

But what happens when Daniel has too much to drink? Well, the alcohol goes to his head and disrupts his normal, sober consciousness — his particular style of attention and control. It changes how he perceives the world and how he behaves within it.

The result is that some of the things he thought were hard, prickly, essential parts of himself turn out not to be so essential after all.

Maybe if he gets drunk once or twice, he can chalk it up to a fluke experience, something he doesn't need to identify with — like when a dentist doses him with nitrous oxide. But if he continues to choose the experience, he'll be forced to acknowledge drunk-Daniel as another facet of his identity. In other words, the choice to get drunk legitimates his drunken identity.

Moving outside the normal range of consciousness has a predictable effect on identity: it shrinks the prickly parts and expands the gooey parts. Here's how it works. Remember that prickles represent the necessary conditions of identity. When Daniel is in a state of altered consciousness, he's attending to the world and behaving in ways that are not part of his sober identity — and yet he's the same person. When he chooses to drink, he must therefore choose to identify with the resulting style of attention and control. In other words, he finds that there are fewer necessary conditions — and more potential states — that are still him.

To make this concrete, Daniel might find himself (while inebriated) sharing intimate details of his life with a perfect stranger. This is something he'd never do sober. Keeping certain things private was, previously, one of his core, inviolable principles — but here he is spilling his guts to someone he just met. A behavior (in this case, being open with strangers) that was once excluded from his prickly identity is no longer excluded. It's now included in his repertoire of potential behaviors, available to him even while sober.

Bottom line: Most drugs don't fry your brain or put holes in it — but they can turn your identity to mush.

To drink or not to drink?

I hope now we understand Daniel's concerns well enough not to trivialize them. We can't just flippantly tell him, "Loosen up buddy!" because there are real consequences. His peers, pressuring him to drink, aren't merely asking him to have a fun experience — they're asking him to change who he really is. (Or at least how he sees himself, which is largely the same thing.)

So what should Daniel do? To drink, or not to drink? If we rule out the mundane reasons not to drink (health, alcoholism in the family, etc.), this becomes equivalent, for Daniel, to asking whether it's better to have a pricklier or gooier identity.

There are at least two significant benefits to being prickly:

- Having a large prickly identity makes you more socially salient. By standing up for yourself, you stand out from the crowd. You create a strong identity, and just as important, a legible identity. This stability and legibility make you a reliable platform for others to build on.

- George Bernard Shaw famously wrote: "The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man." The unreasonable man here is the prickly one. People who are gooey conform themselves too easily to their surroundings, and don't seek to impose themselves on the world.

The prickly people I know are all extremely useful in these two ways.

But clearly there are also benefits to being gooey:

- Having a gooey identity makes you more flexible. We speak of people who "go with the flow," or who are "easy-going." Flexibility makes you easier to work with, more amenable to compromise, more of a "team player." Whenever these things are useful, so is having a small-prickly/large-gooey identity.

- Being gooey leads to having a smaller ego. When ego gets in the way of making good decisions, gooey has the advantage.

- Finally, if Buddhism teaches us anything, it's that having a smaller prickly identity and a larger gooey identity makes us happier. The second of the Four Noble Truths holds that "the origin of suffering is attachment," i.e., prickles. "Let go," the Buddha invites us, "and you will be happy."

Strategic identity construction

Luckily we don't need to make a single, categorical choice between having a prickly self and having a gooey self. We can make separate choices for each component of our identities. So the really important question becomes:

Which parts of your identity should be prickly, vs. which parts gooey?

Deciding where to put something — in the prickly part or the gooey part — depends on what game you're playing and how much you want to win.

The game of morality requires that you put your moral principles in the prickly, uncompromising part of your identity. If you don't, we'll accuse you of having loose (i.e. gooey) morals.

The game of science asks you to put all of your scientific beliefs in the gooey part of your identity, while holding fast and prickly to the principle of truth (and nothing else). To do otherwise — to maintain a scientific belief as part of your core, inviolable, prickly identity — is to sacrifice truth on the altar of ego: the cardinal sin of science.

The game of political debate is played by placing your political beliefs and values in the prickly parts of your identity. Scientifically this is reprehensible, but it seems necessary for winning arguments. (It may also be why science and politics go together like oil and water.) On the other hand, to operate successfully as a politician — to actually get things done, in a very messy world — requires the ability to become gooey at strategic moments.

The game of art — i.e., being an artist, especially of the "high art" variety — requires maintaining a hard (and unique) aesthetic sense. "Selling out" is the accusation we level at an artist who turns gooey in service of commercial success.

The game of art appreciation, on the other hand, is played (optimally) by treating all your aesthetic sensibilities as flexible and gooey. The more you hold fast to liking certain types of things (which, by implication, means you dislike other types of things), the narrower your appreciative range.

We could analyze other games this way (finance, happiness, marriage, acting, etc.), but I think you get the idea. Winning requires strategic identity construction — deciding when to yield and when to prickle.

In conclusion

As much as we might want to criticize Daniel for being too prickly, I'm afraid this leaves us without a strong foothold. The best we can say is that he'd be happier if he loosened up a bit. But happiness comes at a very real social cost (something I wish Buddhists would more readily acknowledge). In the context of Daniel's life — given the games he's playing and the strategies he's chosen for succeeding in them — maybe he's right to stand firm and steel himself against the onslaught of the world.

___

If you liked this essay, you may also like:

- Ethology and Personal Identity (meltingasphalt.com)

- Keep your Identity Small (paulgraham.com)

- Eternal Hypochondria of the Expanding Mind (ribbonfarm.com)

- Alan Watts' Myth of Myself and Man in Nature (youtube.com)

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt