Last week Peter Sobot posted an article about startups as bands for hackers. While that metaphor explains a lot of the startup experience, I think a deeper metaphor is to view startups as frontier communities.

Consider this story of life on the frontier.

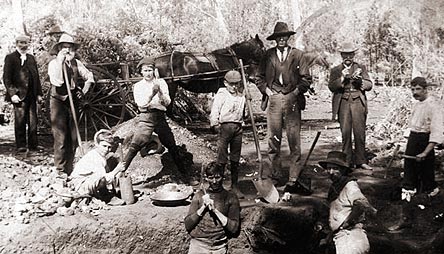

A small tribe of risk-seeking pioneers departs from the comfort and safety of civilized life to strike out on their own. They head west, yearning to explore the uncharted wilderness of (design) space — to use their wits, courage, and relentless resourcefulness to boldly go where none have gone before them. Perhaps others have seen these new lands, but only in passing, on research expeditions — no one has yet been able to settle there. For the tribe's ultimate goal is colonization: to set up permanent camp and build new lives and livelihoods. Eventually (if the economics are sound), they will grow their small, scrappy camp into a territory all its own, luring more and more pioneers with promises of independence, adventure, and yes, wealth. Along the way they will confront a hostile environment, competing tribes, internal conflict, and threats from more settled powers. They will have to grow and change, specialize or take on new roles as their situations demand. If the tribe learns about a better location nearby, they may have to uproot and move camp. They may even fail and disband, choosing either to join other settlements, try to survive on their own, or return to whence they came. If they succeed, it will be through perseverance, efficiency, solidarity, and a healthy dose of luck.

The point is that founding and growing a company is fundamentally an act of exploration and colonization. Steve Blank's definition even encodes this idea: "A startup is a temporary organization in search of a scalable and repeatable business model." First explore (search for a business model), then colonize (repeat at scale).

Like all good metaphors, this provides another lens through which to look at our target domain (startups). Let's dig deeper into some of the mappings to see what ideas the metaphor brings out.

The economics must be sound

History is subject to geology. — Will and Arial Durant, The Lessons of History

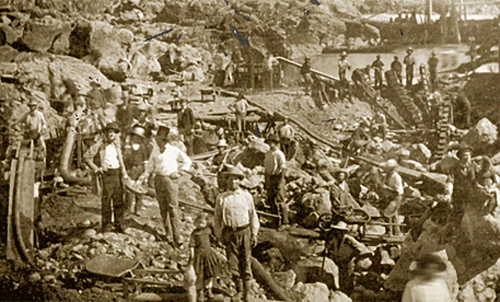

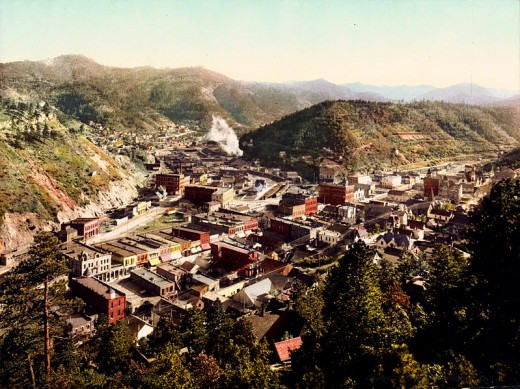

You could try to build a new colony on the Great Plains, but it wouldn't amount to much — the resources just aren't enough to support a massive endeavor. Mining settlements are interesting because they sit on what's clearly an important resource, but if the mines dry up, you're out of luck. The best settlements grow — one might say crystallize — around the most enduring resources: rivers and ports, or important overland trade routes. Location exerts a tremendous constraint on how big a settlement can grow. Having the right people, culture, and institutions will only take you so far on the North American steppe or high seas.

Similarly, if you want to build your startup into an empire you'll need to find a truly important problem. Despite all the fuss about execution over ideas, execution alone won't produce the next Facebook or Google.

Let's look at some recent startups and the resources they staked out and then colonized. Google took web search — clearly a pivotal, enduring resource. Twitter colonized real-time status updates. Quora is attempting to colonize Q&A; it remains to be seen how central and enduring such a claim is. Facebook of course colonized online identity. What may not have been obvious though, ex ante, is that there are actually multiple online identities to colonize, spaced sufficiently far apart to allow — require? — multiple settlements. Here I'm talking about personal identity, professional identity, and the weirdly myriad dating identities.

Microsoft colonized the personal computer and were wildly successful at it, but now they're afraid that the niche is drying up and moving webward. (And they ought to be afraid — I'm composing this essay on my Google Drive, using Google's primitive, but eminently serviceable, web-based document editor.)

The logic of the frontier

Frontier refers to an area near or beyond a geopolitical boundary. In the case of the American (land) frontier, it referred to the fluctuating area at the fringe of official state control, primarily during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the startup community, the frontier represents markets and technologies just at the fringe of control by the bigger, more established players.

But the frontier isn't just empty space. It's the entire environment (or niche) where many forces converge. And these forces exert pressure not just on those who live and breathe the frontier, but also on the folks 'back home.'

Writing about how frontiers have shaped American society, Daniel Elazar identifies ten basic conditions that appear in every frontier situation. I'll quote the entirety of it, because nearly all of these conditions pertain to the tech frontier as well:

- The frontier involves extensive new organization of the uses of the land, uses so new that they are essentially unprecedented but so much a part of the process in question that they will be applied across the length and breadth of the continent during the course of frontier expansion.

- Frontier activities are those devoted to the exploration of that which was previously unknown and the development of that which was previously "wild" or undeveloped.

- There must be an expanding, or growth, economy based on the application of existing technologies in new communities or new technologies in existing communities.

- The frontier movement, though manifesting itself as a single "whole," actually coalesces a number of different "frontiers" both geographic and functional. These exist simultaneously and successively, each with its own goals, interests, character, and pioneers, yet all tied together by their common link to the central goals, interests, and character of the large frontier of which they are parts.

- There must be the opportunity to grow, change, risk, develop and explore within the framework of the frontier, thereby increasing freedom from past restraints and demanding courageous action.

- There must be reasonably free access to the frontier sector of society for all who want it; and migration must be a major factor in gaining that access.

- A frontier situation generates a psychological orientation toward the frontier on the part of the people engaged in conquering it, endowing them with the "frontier spirit."

- The "feedback" from the frontier leads to the continuous creation of new opportunities on many levels of society, including new occupations to be filled by people who have the skills to do so regardless of such factors as family background, social class, or personal influence, thus contributing to the maintenance or extension of equality in the social order.

- The frontier feedback must influence the total social structure to the point where society as a whole is significantly remade.

- The direct manifestation of the frontier can be found in every section of the country at some time (usually sequentially) and are visible in a substantial number of localities which either have, or are themselves, frontier zones.

Almost all of these concepts apply to the tech frontier, but my favorite is #7. It's clear to anyone who sets up camp in Silicon Valley (and in startup hubs all over the world, I'm sure) that there's a "frontier spirit" in the air. It's an optimism, a can-do (and DIY) attitude, a thirst for the future.

Another important property of the frontier is its lawlessness. If the law is congealed power, its absence means freedom, and freedom is essential to how the frontier and its inhabitants operate. It's not that startups flout the law (although some of them skirt it), but rather they operate in areas where the law hasn't (yet) stifled innovation. The entire internet has been relatively unregulated so far (knock on wood), which has meant tremendous freedom and an unprecedented amount of innovation. PayPal also provides a great illustration: They began as a relatively unregulated entity, but the law (for processing online payments) soon caught up. Sadly, it would be much harder today, if not outright impossible, to start an online payments business.

Tribal psychology

The frontier is one of the most interesting human niches. It draws a particular type of person, and once drawn, exerts a constant psychological and behavioral pressure (as niches tend to do).

People drawn to the frontier choose to leave their calm, predictable, safe lives and head west. These pioneers tend to be risk-seeking (either for the chance at reward, for the adventure itself, or some combination of the two), strong, pragmatic, skilled (often at many different things), open to change and new ideas, and relatively distrustful of authority in all its guises.

But the influence of the frontier doesn't end at the individual. The frontier also shapes the cultures of the tribes who inhabit it.

The most striking effect is forcing solidarity. Out on the fringe, short on resources and surrounded by wilderness and potential enemies, a tribe must either unite or perish. Most tribes — and certainly all the successful ones — figure out how to unite.

The effects of solidarity should not be underestimated, either in geopolitics or on the Darwinian battlefield of corporate competition. In War and Peace and War, Peter Turchin argues that all the world's great empires germinated on a frontier:

[Frontier peoples] become characterized by cooperation and a high capacity for collective action, which in turn enables them to build large and powerful territorial states.... Cooperation provides the basis for imperial power.

I don't have any real data to back it up, but intuition tells me this is true in the tech community as well. The healthiest startups (as well as established companies) seem to be those with the strongest cultures, which align everyone and keep politics to a minimum. I work at Palantir, which has excelled in many ways, but I often think our culture is our biggest asset. There's also Apple (a completely different, but equally strong culture), Facebook, and Google. (Google's culture was a dominant force in Silicon Valley for many years, but it may be on the decline now.)

The frontier also tends to forge tribes that are more democratic and meritocratic (and less status-conscious), have fewer laws and policies, and bias toward empiricism over theory (because theory encodes facts about older environments). All of these cultural institutions help keep tribes more flexible, so they're more able to adapt when change inevitably comes.

One of the biggest changes a tribe will face is its own growth, and it's culture will shift as a result. Speaking about the lifecycle of a company, Robert Cringely put it well: Commandos give way to infantry, who give way eventually to police.

Here are some other changes that can occur as a pioneer settlement or a startup becomes more established:

- Increased specialization. Pioneers start out as generalists, but economies of scale will soon insist that they specialize. With growth, what was once the province of an individual will become a whole group dedicated to that single function. New roles will appear just to handle the size and complexity of the community (newspapers and banks; HR and corporate finance).

- Increased caution. As the company or settlement matures, it will acquire real resources in need of protection. The spirit of risk-taking that drove the initial growth will be in danger of receding.

- More law and policy will be created, and the community will develop a more legalistic attitude. What originally would have been settled with a conversation or confrontation will soon be decided by policy, precedent, or the courts.

- The community will become more stratified and status-conscious. Politics will become more important and visible.

- The community will become less vulgar. Decorum will find its place.

- Local settled powers will come looking for appeasements — and the appeasements will usually be made.

- Success will attract people looking for a quick buck. Cheaters and charlatans will find it easier to slip into the cracks and make (temporary) homes for themselves.

For a growing startup, none of these changes are destined to occur. But there will always be pressure pushing the group in these directions, and it will require constant discipline and vigilance to make sure the culture stays healthy.

Where the metaphor breaks down

No metaphor is perfect. One of this metaphor's biggest shortcomings is that meatspace pioneers don't usually end up owning more than the merest sliver of the total value of their new colony. The difficulty of capturing future wealth also explains why real settlers don't usually have backers/sponsors (i.e. VCs).

Another difference between working for a startup and being a pioneer is that success at a startup demands much tighter coordination among its members. In a small settlement, it may be enough for people simply not to work at cross-purposes — and to band together during a crisis, of course.

If you want to focus on the coordination that needs to happen at a startup, you might use the lens of another conceptual metaphor: the one that says companies are like ships (see e.g. page 5).

Final thoughts

Pioneer groups aren't the only ones trying to colonize new regions of design space. Sometimes a more established player (Apple for example) will make an attempt. Their advantage is having a huge, well-oiled machine with effectively unlimited resources. Their disadvantage is psychological — they are often too cautious, inflexible, or slow, or they get hamstrung by internal politics. For an established player, finding the right way to do sponsored colonization is tricky, but crucial to long-term growth. If an organization can't do its own colonizing, then it must learn how to annex (i.e. acquire), or be content with its current holdings.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt